If you enjoy this post, please retweet it.

By now, most of you nerds must be aware of the newest incarnation of TSR (“newer TSR”). They exist despite the fact that the new TSR (ummmm, “new TSR”) hasn’t died yet. Among other well-known gaming people, Ernie Gygax serves as Executive Vice President. The idea behind the newer TSR is to recapture the magic (get it?!) of the old days of the original TSR and Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. Unfortunately, Ernie casted Dispel Magic in an interview that ruffled a lot of feathers. I’m not commenting on that. As I’ve said, this is a not a blog for political issues, matters of human rights, or nuclear war. That’s way too heavy for this blog. Besides, do you really need yet another voice in this massive choir of commenters? No, so instead I’m going to discuss an aspect of IP law that’s probably relevant to the case and many of you may not know.

Disclaimer

Okay, you knew this was coming, but it’s especially important here. This is not legal advice. All I’m doing is stating the law in the abstract. If someone, including either or the two TSRs, thinks it applies to their facts, then they can hire an attorney to get legal advice. But isn’t stating the law legal advice? No, it’s not. Anyone can state what the law is (e.g., “The speed limit is 55 mph.”). Only attorneys can apply that law to another person’s fact pattern (e.g., “The speed limit is 55 mph, you’re driving 65 mph, and therefore you’re violating the law.”). No district attorney is going to prosecute you for telling someone they’re speeding, but this is an easily digestible example to define “practice of law.” This is key here because I strongly suspect that I have only a fraction of the facts surrounding this case, so it would be impossible for me to practice law here. So I ain’t. Got it?

I’m My Own Inspiration, aka, The Tweet Heard ’round the World

This blog post was ultimately inspired by, well, me. That is, it was inspired by my response to Luke Gygax’s tweets with which many of you are familiar. Of course I was deflecting from the actual topic to the law. It’s what I do.

Trademarks and the Constitution

Oh, you thought you were going to get through this without any heavy-handed legal philosophy, didn’t you? Here’s some constitutional law, suckers.

The US Constitution defines a government of limited powers. That is, unlike the states, the federal government lacks power unless 1) the US Constitution expressly says it has that power; or 2) the federal government absolutely must have that power in order to use a power that the US Constitution expressly says it has. As for number two, nowhere does the US Constitution say that the feds have the power to enter into employment contracts, yet they must have that power in order to, for example, create the IRS and hire accountants, admin assistants, janitors, etc., because otherwise the power to collect taxes would be rendered useless.

This is not a controversial statement among lawyers, though lawyers are (believe it or not) human, so many of them sometimes ignore this principle as well because . . . okay, no pontificating. The notion that the feds lack the power to act by default seems to be lost on many people, but there it is. Accept it or deny it, but it’s 100% true.

Okay, back on point, the Arts & Sciences Clause grants the federal government the power to grant patents and copyrights, but it doesn’t mention trademarks. That’s left largely to the states. (Weird, huh? When have you ever heard of state trademarks?) However, there’s a back door that gets the feds into that game. The Commerce Clause allows the feds to regulate “interstate commerce” (i.e., business transactions that cross state lines). If a vendor in Arizona sells something to a consumer in Utah, then that sale could open the door to federal regulation even if the feds don’t otherwise have the power to stick their noses into it. So, the Lanham Act provides for federal registration of trademarks with the US Patent and Trademark Office only if the owner is using their trademark in multiple jurisdictions. If you’re using the trademark in only one state, you don’t qualify for a federal trademark. However, if you do qualify for a federal trademark, it applies across the entire United States. (Well, almost, which will be my ultimate point.)

There’s a limited exception for those with an “intent to use,” but I’ve given you enough to digest.

So what happens if you don’t register your trademark federally? As long as you’re using the trademark in commerce, you develop “common law trademark rights,” but unlike the federal trademark rights, those rights apply only in the jurisdiction or region where you’ve been using the trademark.

If you’re doing business in a large state, common law trademark rights may arise only in your local region. In that case, registering your trademark with that Secretary of State for that state would grant you trademark rights across the entire state.

Seniority of Trademarks

Okay, I’m finally approaching my point. Imagine a situation where I’m using a trademark, Bodine’s Bovines, on my cow farm in Virginia. Therefore, I have trademark rights only in Virginia. Only I can use that trademark in Virginia.

Next, Fred Bodine (no relation) opens a couple of cow farms, one in Utah and one in Nevada, both using the same Bodine’s Bovines trademark. He registers the trademark federally based on his use across state lines, so now he has a trademark that applies across the entire United States. Finally, I decide to open a second farm in North Carolina. I try to register my trademark federally, but Fred beat me to it, so my application is denied. Also, Fred sends me a cease-and-desist letter preventing me from using Bodine’s Bovines at all. Does he have a right to do that? In North Carolina, yes, but in Virginia, no. I opened my Virginia farm first, and even though I never registered the trademark with either the feds or even the Commonwealth of Virginia, my use in Virginia was “senior” to Fred’s use (i.e., because I used it in Virginia first). However, Fred can block me from using it outside Virginia because he registered the trademark federally before I opened the North Carolina farm.

What if instead I had a federal trademark based on prior use both in Virginia and North Carolina, let it lapse, and then Fred came along and grabbed it based on his use in Utah and Nevada? I’d still have senior rights in both Virginia and North Carolina.

So, you can think of a federal registration as having the same effect of using the trademark in every state starting at the time you registered it. Where you got there first, you get to use it, but you’re blocked where you didn’t get there first. In a more complex case, you could imagine a patchwork of multiple, identical trademarks being used by several different companies in several jurisdictions, with one of those companies having a federal trademark covering the unclaimed jurisdictions. So, the company with the federal trademark could nevertheless be blocked from using that trademark in jurisdictions with senior users. This isn’t a far-fetched scenario, but if its mere possibility surprises you, then . . . surprise!

So, what happens next? Well, when the two parties each have something the other wants, they could strike a deal. For example, each could license the other the right to use their trademark in jurisdictions in which they’d otherwise be prevented from marketing. If both parties are on relatively equal footing, the license fee may be, I don’t know, as small as $10 per year. However, if one party doesn’t realize how much of an advantage they have or lack the funds to enforce their advantage, they may make the same deal.

Sound familiar? No? Well, too bad. I’m not getting into specific cases. 🙂

Epilogue

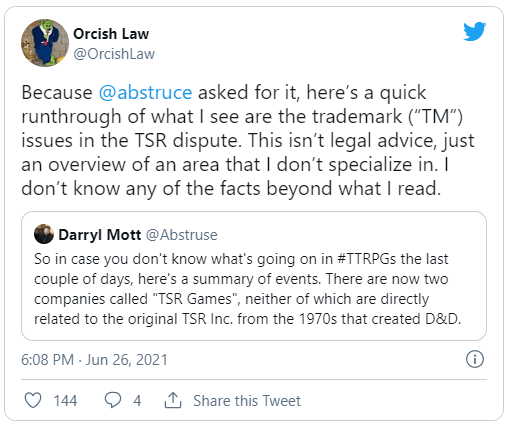

After completing this post, I found a relevant Twitter thread.

There’s a lot of overlap, but Orcish Law makes a few other relevant legal points and peppers in a lot more gifs. I left much of that out because I have a tendency to ramble, so I try to keep my posts as short as possible. We both included disclaimers though. It’s what we do.

If the trademark is valuable, and you can afford a lawyer, get one. Otherwise, you’ll have to either cut a bad deal or find a new trademark.

Follow me on Twitter @gsllc

Follow Luke Gygax @lukegygax

Follow the newer TSR Games @TSR_games

Follow the new TSR @tsrgames

Follow Ernie Gary Gygax, Jr. @Gygax_Jr

Follow Jayson Elliott @JaysonElliot

Follow Orcish Law @OrcishLaw

Dungeons & Dragons is a trademark of Wizards of the Coast, LLC, who neither contributed to nor endorsed the contents of this post. (Okay, jackasses?)

In case the tweets are deleted, here are images of them: