If you enjoy this post, please retweet it (Twitter/X), boost it (Mastodon), repost it (MeWe), or repost it (BlueSky).

I did a thing.

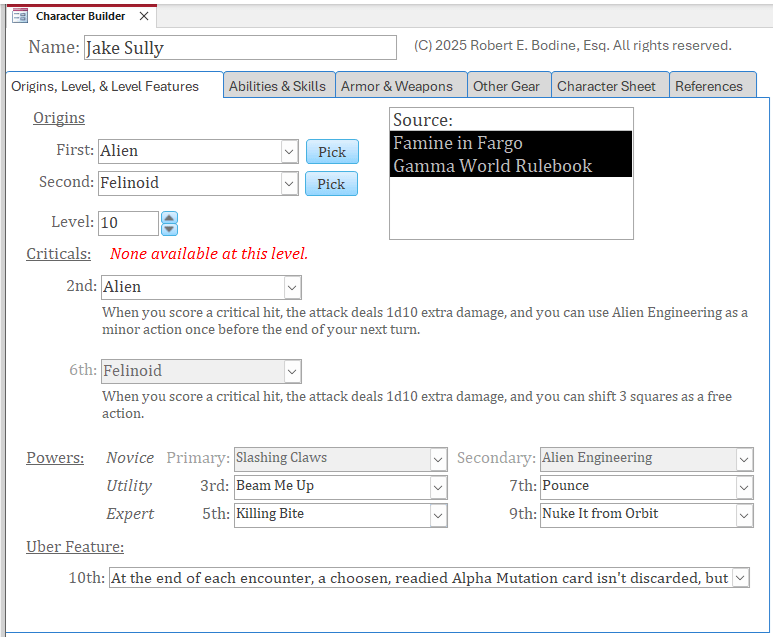

Over the past week or so, I created a character builder for 4th edition Gamma World. Well, really, 7th edition, but because it was based on the 4e Dungeons & Dragons system, it’s often referred to as 4th edition by non-enthusiasts like me. I’ve never played any other editions, though I owned some books at some point.

Anyway, you might be asking, “One week?” Well, yeah. I get that. My 1e Dungeons & Dragons campaign manager took years to create. The data entry was a royal pain in the ass, and the system is so loaded with exceptions to the rules (rules that themselves weren’t “clean”) that without formal requirements analysis, I made some regrettable design decisions for which I’m still paying. Moreover, there’s no way I could distribute it to the general public even though it creates wonderful character sheets. Only a software engineer could hope to make sense of it. The general public would be lost. None of this should surprise you considering I have a job.

So how the hell did I (essentially) finish the Gamma World project in one week? Well, for one, I ignored my cats.

Second, it’s not like I have anything else going on. Moving on, it’s not a campaign manager. I’ve entered no monsters (yet), and there are no tools to help run the campaign. Also, the game system is really simple. There are no choices to be made. If you’re a radioactive hawkoid, you’re assigned powers, and you don’t get much of a choice in the matter. The only choices you make are, at certain levels, which are very limited. For example, the aforementioned character has two origins, hawkoid and radioactive. Each grants a single utility power, one option per origin. If you choose the hawkoid one at level 3, then you must choose the radioactive one at level 7. This is true of critical hit effects and expert powers at different level pairs. it’s not like 4e where at X level you have several powers from which to choose. There’s only one or two options, and where there are two, choosing one forces you to choose the second later on. That’s great for software designers, especially ones 25 years removed from the industry and forced to use MS Access for the whole thing. It’s almost like automating tic-tac-toe, and even Access can facilitate that. (Access has way too many issues to use commercially, the absolute worst of which is the fact that you can’t embed commas or semicolons in text fields that will ever get loaded into a listbox. WTF?!)

Other than little tweaks here and there, the only thing I need to do is give the ability to save and load characters to and from the hard drive. You might think that’s a fairly important feature, but no, it’s not. Gamma World character creation is so easy that rebuilding the character from scratch is trivial as long as you saved your prior character sheet showing the gear you found. That’s the whole “great for software designers” thing in action. I can say I’m finished even if I’m not really finished. In fact, I don’t ever need to finish and would still be able to publish this. (I will finish, but that’s not the point.)

Prove It!

Okay, so you want proof? Here are some screenshots.

What you can see is that the builder allows you to limit your sources to the Gamma World rulebook, Famine in Far-go, or both. Also, if there are any supplements I missed, or if you have homebrew content, you could create it and restrict it. For example, there’s some chatter about GW needing errata. So, if you want to change an origin to suit your needs, you can create it within your own source.

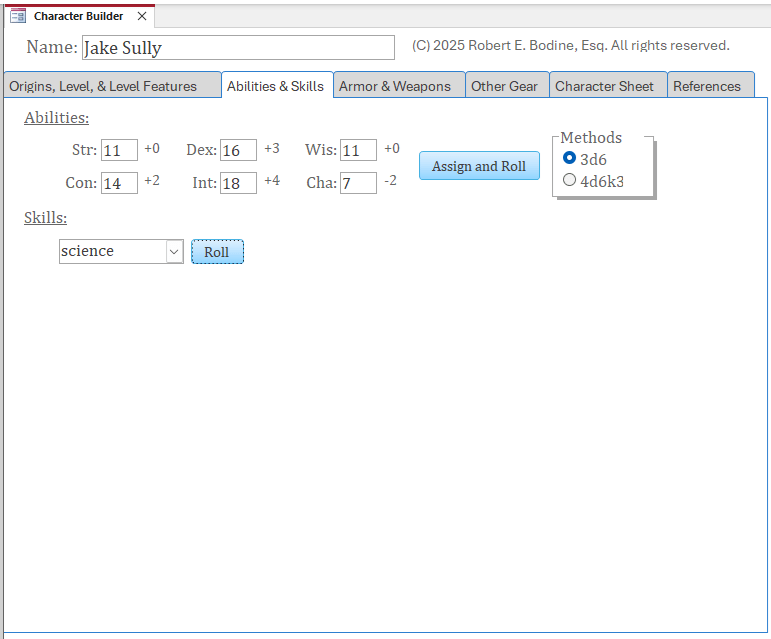

This page is pretty straightforward. I added a “roll 4d6 and drop the lowest” just for the hell of it. It’s not an option in the official rules, but it’s easy to program and just as easy for the user to ignore.

Here you can simply select the type of weapon you have as an abstract concept, or you can add a label for it giving the weapons more concrete descriptions. A lot of this is intended to be abstracted, but one of my favorite Gamma World images comes from a prior addition. A guy using a speed limit sign as a shield perfectly encapsulates the campaign setting. <Googles>

That’s from the 3e GM’s screen. While I haven’t given you that option — as you’ll see, it would have no place on the character sheet — I thought it would be a neat idea to do so for the weapons.

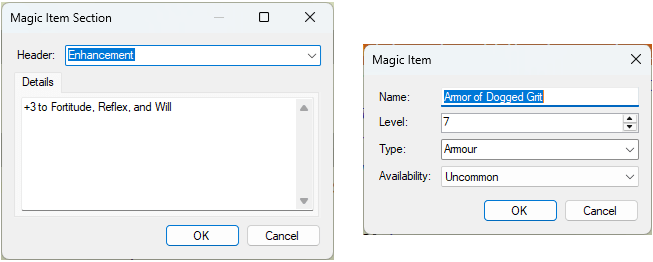

Next up, you randomly roll starting gear, move it into the gear you own, then double-click on any gear or ancient junk you find during adventuring. I had to make a command decision on this one. It bugs me a bit, but it really won’t affect anyone’s lives. Sometimes you roll such that the result is, “Roll twice on this table.” So, you essentially get a bonus item. Technically, under the rules, one or both of those rolls could have the same result, however unlikely, allowing you third, fourth, or twentieth bonus item. For programming reasons, I decided not to allow this cascade. If you get to roll twice, neither of those rolls can give you the result of rolling twice. Similarly, there’s a result that says you can roll twice on the ancient junk table instead. If you do that, you can get a result for either or both rolls allowing you to roll twice, and that’s supported. However, when making your bonus rolls on ancient junk, I block the result of rolling twice. I’m sure everyone will get over it.

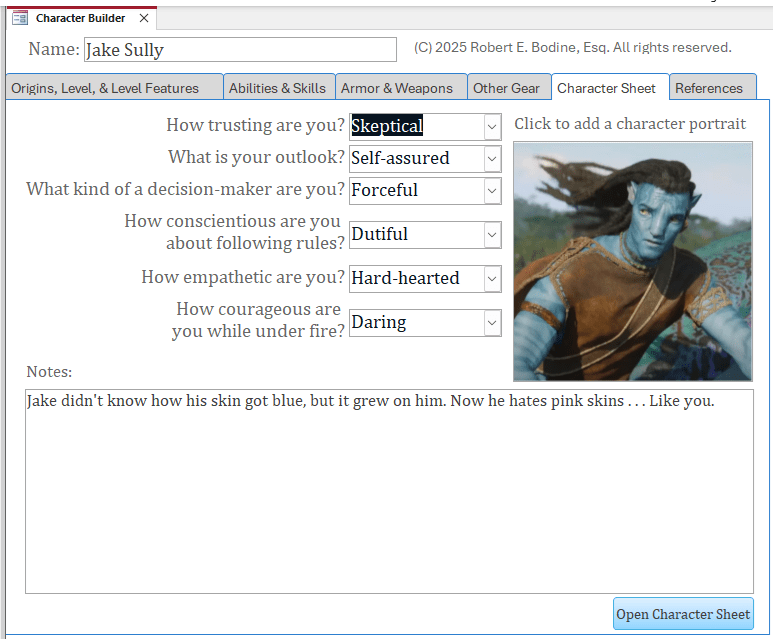

Here, you select your basic personality characteristics, choose your portrait, and enter in any notes. Going back to the prior screen, you can add as many items as you want, but they may not fit on the character sheet. The notes field is good for making sure you can see all your gear and junk on the character sheet. On the character sheet, the notes field will expand forever. Not sure what I mean? Here’s the character sheet for Jake.

How Can I Get a Hold of This?

I don’t know exactly when I’ll distribute the character builder, but it’s taken almost no time to put this together, so a good, working copy should hit GitHub in the near future. Every now I then, I spot an error, and its source can be programming logic or data entry error. Things look pretty clean, but since producing the character sheet, I noticed AC wasn’t taking the Int/Dex bonus into account for Jake, who was wearing light armor.

I really hope I get to make use of it. 🙂

Follow me on Twitter/X @gsllc

Follow me on Mastadon chirp.enworld.org/@gsllc

Follow me on MeWe robertbodine.52

Follow me on Blue Sky @robbodine