Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 3.5 | FAQ/FRI

In case it isn’t clear, Wizards of the Coast (“WotC”) does not endorse this post or any work I’ve created. My use of their trademarks is purely to identify the subject of this discussion and should not be taken as an endorsement of my work by WotC. To the extent that there has been any technical infringement of a WotC copyright by this post, such use constitutes commentary on a de minimus amount of their copyrights and is therefore a fair use of those copyrights.

Also note that this post does not constitute legal advice. This addresses WotC’s copyright misuse; it doesn’t, and in fact can’t, address whether any actions of the reader themselves constitute copyright infringement. If the courts find copyright misuse, then the copyrights will be deemed unenforceable retroactively to the point in time when the misuse began (likely 2005 or earlier). If the courts don’t find copyright misuse, then past infringement is still subject to a lawsuit, and this post doesn’t address anyone’s behavior other than my own. Your case rests on your facts. If there’s any concern that you’ve infringed WotC’s copyrights, you’ll need to retain an attorney.

Unsurprisingly, these three articles have generated a lot of questions and concerns. This is an attempt to address as many of these as feasible. If you post comments below, I’ll answer even more

Killing WotC

From Twitter: “Wizards of the Coast one day will fall. We are a day closer to that day.”

First, I don’t think that these posts and any litigation that comes from it will significantly damage WotC. They’ll just be forced to adapt, as will the rest of the industry when those other companies realize that WotC’s “leadership” was just self-serving manipulation. Besides, WotC themselves admit that freely distributing some of their material isn’t bad. Setups and misstatements of the law aside, they’ve claimed to have done so with the SRD. They’ve freely given away some class writeups for which copyrightability can be reasonably argued. Ultimately, WotC should be fine.

Second, I’d be greatly disappointed if this did kill WotC, so I don’t agree with the sentiment at all.

Third, we all better hope this doesn’t kill WotC. As I said, the entire industry will be forced to adapt. If that’s not possible for WotC, then it isn’t possible for anyone else. Do you actually want the entire gaming industry to collapse? I don’t.

Assuming a Total Loss for WotC, What Are the Consequences to the Industry?

You’re asking the wrong guy. I have my speculations, but they’re probably no better than your own. However, for the record, here’s what I suspect, which should be addressed by industry professionals.

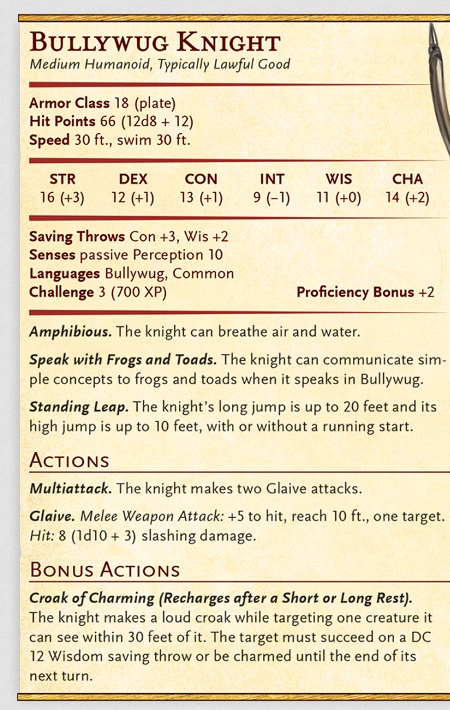

Gaming companies will be forced to abandon books like the Monster Manual and focus more on books like Volo’s Guide to Monsters. Rather than mass produce monster stat blocks, they need to focus on cultures, backstories, storylines, etc. of those monsters, making sure that whatever stat blocks are provided don’t represent the impetus for buying the book. This in turn means that their game systems will have to be written in a way that players can quickly and intuitively design their own monsters. If they don’t, the game will be unplayable. Many designers have added unnecessary complexity to their mathematical systems in order to assure a market for bestiaries, and convinced the community that this was necessary to make the game fun. Now that this is no longer an option, they’ll need to come clean and prove otherwise.

So, the question to ask any professional game designer you know is this: Can you produce a game subject to the constraints outlined above that’s still fun to play? If the answer is yes, no one’s life or profit margin will change significantly.

Stat Blocks Aren’t Facts

An attorney took me to task for characterizing stat blocks as facts. In the copyright context, facts are things that no human being created, such as the circumference of Saturn. Stat blocks aren’t strictly facts. Instead, they’re human creations that aren’t creative enough to rise to the level of copyrightability. Those are two different things. With facts, there’s no analysis of creativity. They simply aren’t copyrightable from the get-go. With low-creativity creations, you must perform that analysis to determine whether they’re copyrightable. This is 100% true.

However, once you determine that creative works aren’t copyrightable, from that moment forward in the conversation, they’re indistinguishable from facts. The only important aspect to either at that point is that they’re uncopyrightable, so I could fairly use “facts” as shorthand to represent both. Everything I said about one would apply to the other.

What the attorney didn’t fully appreciate is that I was writing this for two very distinct audiences, attorneys and laymen, each of whom needed to hear different things. However, when in doubt, I favored the laymen. They had to understand what I was saying, and if simplifying my language was helpful in that regard, then that was the best way to write it. It wouldn’t affect an attorney’s understanding of what I was writing because attorneys would still be aware of the distinction.

In fairness to the commenting attorney, at the point that I first referred to stat blocks as “facts,” I hadn’t yet established that they were uncopyrightable. In legal writing, we tend to state our conclusions first so that the reader knows where were going, and then the justification follows. However, my justification had to cover a lot of ground, over half of which was reserved for post #2, so by frontloading my designation of stat blocks as facts, and failing to conclude my argument by the end of the post, it appeared I was missing that distinction. Was that a bad approach to take?

If so, take it up with Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. She did the same thing in Feist. Phone numbers were referred to as facts throughout her opinion, signed onto by seven other justices (Justice Blackman concurred without explanation). Are phone numbers facts? Do you expect to find phone numbers growing in the bushes during your hikes through the wilderness? Of course not. A human (or a human’s software) at the telephone company selects a phone number (subject to area code and exchange constraints) and assigns it to a person. They could choose from a large number of phone numbers but choose one in particular. Their status as a phone number occurs only after someone at that phone company creatively selected and assigned it as such. While the raw number exists in nature, its status as a “phone number” has some small amount of creativity. It just isn’t creative enough, and because the question of creativity was a side matter in that case, Justice O’Connor chose to use the same shorthand even though her primary audience consisted of attorneys. One could also interpret her opinion as saying telephone numbers “become facts” once assigned, so by the time the phone company places it in a phone book, it becomes a fact. I think this would be a strange interpretation, but assuming that’s the case, it doesn’t reduce the strength of it’s comparison to stat blocks, because one could say the same thing about them. Under the same logic, stat blocks become facts once WotC creates them, so a compilation of stat blocks remains uncopyrightable (despite appearing alongside copyrightable elements in the Monster Manual, etc.).

This isn’t the only time that I played a little loose with copyright law. For example, in the discussion of the slaad, I suggest that the idea of a slaad can be copyrighted. The idea of a spy can’t be copyrighted, but the character of a specific spy, James Bond, can be. What’s a slaad? Is it an idea or a character? To be precise, it’s a species, which seems to make it an idea, but it’s completely make-believe, which one could characterize as a bunch of specific characters. I didn’t want to get into this abstraction/reification debate because it wasn’t important to my point, so as I did in a few other places, I simply assumed WotC had a possible copyright, then asked, “So what?” I then moved onto why that wouldn’t matter. Copyright can be complex, and I certainly covered enough to make the average gamer’s head spin.

To the extent I confused any of the laymen reading this, I apologize, but I have a feeling that this discussion has as much potential to confuse you than what I wrote in my first post.

Complexity and Non-Stock Abilities

It may seem counter-intuitive that the more complex a system gets, the less it enjoys copyright protection. At the extreme end of the complexity spectrum, this actually makes sense, but the explanation gets a little weird.

In science, an “emergent property” refers to a characteristic that a group has that the individuals comprising that group do not have. A looser definition is something that rises from extreme complexity, where the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts. Consciousness is thought to be an emergent property of the vast number of neural connections in the brain. Civilization is an emergent property of the vast number of human relationships when bound together in a relatively small area. Similarly, the concept of magic is so complex at this point that even truly original combinations are nevertheless contemplated by copyright law, disqualifying them for protection.

I think this is what the DaVinci Court was trying to say with respect to non-stock abilities but couldn’t because the subject matter didn’t lead to the proper argument. Even if there has never existed the fantasy element of an elf that was said to have the power of invisibility, the massive complexity of the concept of magic trivially implies such an element. Dwarves have done it, humans have done it, dragons have done it, oni have done it, fungi have done it, etc. Thus, even if you were literally the first person to create an elf that could turn invisible, while technically creative, it’s not nearly creative enough. You can think of it this way: The DaVinci Court assumes (rather reasonably, I believe) that you must have been considering all of those creatures being able to turn invisible when you decided an elf could too. Ergo, while technically creative, it isn’t creative enough. There’s just been too much done with magic to think that your contribution to art was copyrightable. In this respect, the concept of what magic includes outpaces the ideas that have been literally expressed.

What about a spell that’s never been contemplated before? Let’s say that each of those creatures (except the elf) had the D&D 5e version of invisibility. It lasts until you cast another spell or attack. Let’s also assume that we’ve seen creatures that can fly, charm a person, or push them away, but that doesn’t go away when they cast another spell or attack. How much of a creative leap is it to come up with an elf that can 1) turn invisible, and 2) stay invisible even after it casts a spell or attacks? Considering that we’ve seen all manner of creatures cast all manner of spells, and that we’ve seen all manner of creatures be able to sustain spell effects even after casting another spell or attacking, the leap isn’t great enough. In fact, it naturally follows from how the typical person defines magic. This necessary implication is something akin to an emergent property of the total body of magic as imagined. Perhaps it fits the definition of an emergent property perfectly. I’ll allow the scientists to debate that.

That’s why even non-stock abilities shouldn’t be protected. Even original combinations of abilities are easily contemplated based on the nature of magic and spells, such that those original combinations aren’t creative enough to justify a copyright. If the games in those court cases were RPGs, I’m sure that’s what the courts would have said (in different words).

The Pattern of Bad Behavior and Cultivating Misinformation

I referenced WotC’s pattern of bad behavior without being able to pin down how far back it went. I also claimed that WotC has cultivated a misunderstanding as to what third parties can and cannot publish. These were based purely on my experiences over the years, most of which I expect most readers to have shared, and so I provided little support for them. About four hours after I published the third post, I found some of that evidence.

In 2004, WotC published a FAQ (last visited 8/26/2019) explaining their interpretation of the 3rd Edition OGL. Among other things, the FAQ states that Open Game Content “cannot be something that is in the public domain,” but the 3rd Edition OGL itself defined Open Game Content as including “the game mechanics and includes methods, procedures, processes and routines . . . .” Unless WotC is under the mistaken impression that it was granted a patent in the d20 mechanics without having ever applied for one, how could they possibly think any of those things weren’t in the public domain? In another hypothetical question, WotC was asked if the terms were unfair, and their answer was, “If you don’t like the terms of the Open Game License, don’t publish Open Game Content.” Remember, this includes the game mechanic.

WotC also claimed that a user could identify a character’s name as “Product Identity,” thus prohibiting its distribution. WotC was stating the position that a character name could be deemed copyrightable. I suppose their “out” is that they were contemplating the name being used as a trademark, but the specific example given was that of a character name being used in a stat block. At the very least, WotC was suggesting to laymen that names could be copyrighted as well. In the context of the prior three posts, it appears they were attempting to protect their perceived interest in names of characters and creatures. Again, we’re not inside their heads, but the evidence is strong, and ultimately their actions will be more important than their motives.

Moving forward to the less comprehensive 5th edition FAQ (last visited 8/26/2019), the second frequently asked question provides an answer that shows intent to make the 5th Edition OGL a continuation of the 3rd Edition OGL. Keep in mind that the OGL still applies to 3rd Edition, and it appears that WotC’s general approach to the subject matter has remained unchanged.

In fairness, I will say one thing in their favor (without being too nice about it): They also answer the first question with, “The goal of the SRD is to allow users to create new content, not to replicate the text of the whole game.” This is the noble goal I referred to in part 2. In most cases, do you really need to republish what WotC has already provided? What does that do other than to harm the creators’ market for their IP? If you’re going to publish gaming material, make sure you’re introducing something new that isn’t yet available. Be a help, not a hindrance.

But here’s the not-so-nice part: That’s exactly what the one-stop stat blocks did. They provided a form of the stat block that WotC wouldn’t provide and did so only to the extent necessary to fulfill its mission. In doing so, they made the game more accessible to several DMs. You may personally not have use for them, but everyone is different. I won’t run games without them.

My Intentions

As these posts have circulated, I’ve been accused of bad intent; specifically: 1) I picked a fight; 2) I’m trying to take the easy way out; 3) I’m manipulating the law to do an immoral thing; 4) I’m out to destroy WotC; and 5) that I’m in it for the money and my talk about the public good is empty. Some of those critics were clearly just trolling, but not all. Most of you don’t know me, so you have no way to sense my motives. These are all fair concerns, and all I can do is address them here. Believe it or don’t.

I Picked a Fight

No, I didn’t. WotC threatened me. Based on the context of everything I’ve written, let’s summarize the turn of events leading to us to where we are.

- I did something that was 100% legal but had the potential to harm WotC;

- I carefully crafted that thing to make sure that it didn’t damage WotC’s sales, as it was still necessary to purchase the Sourcebooks in order to play the game;

- If I had a broader footprint, what I did had the potential to help WotC’s sales; and then

- WotC threw its customary temper tantrum.

As I’ve established, stat blocks as currently written aren’t copyrightable, so I could have copied every single WotC stat block in existence and republished them. In fact, I was asked to do that, which I refused (catching heat in the process from some unappreciative fools). Instead, I released them only as PDFs, and I released only those stat blocks that required the one-stop treatment (i.e., ones with Spellcasting or Innate Spellcasting). This made the game more accessible for people like me, which meant that more people would be willing to play more often, as well as invest in the game. Again, my footprint is too small to be significant, but the point is that I could only help, not hurt.

That said, WotC’s reaction wasn’t thought through at all. I received a mild demand to take down the stat blocks, but based on their history of intimidation, it wasn’t something that could be ignored. It was a short email but somehow managed to make as many factual errors as it had sentences. This is their modus operandi. They see material related to 5th Edition Dungeons & Dragons, they don’t see a copy of the OGL attached, and so they threaten before researching that material.

This is 100% on them. If they had left me alone, I probably wouldn’t have written these posts. If they don’t sue me, there’ll be no lawsuit and no GoFundMe. I just want everyone to be crystal clear about the fact that if they do sue me, I’m prepared to go all in. If no one contributes to the GoFundMe, I still won’t back down.

Taking the Easy Way Out

This project has taken years. I didn’t make photocopies of the Sourcebooks. This was a ton of work, and I’ll never make a dime from selling these OSSBs even if a legal ruling in my favor allows me to do so. There was nothing easy about it.

Legal Manipulation and the Destruction of WotC

I’ve been asked what gives me the right to take down the D&D empire that was built through blood, sweat, tears, a brilliant strategy. Let’s say that WotC, through hard work and intellectual superiority, created and implemented an ingenious business plan to steal money from the elderly’s trust funds, and in doing so built an empire. Would you still be asking that question? Clearly not. If the empire is built on an immoral foundation, there’s absolutely nothing immoral about toppling it.

Of course, WotC isn’t stealing money from the elderly. They aren’t even committing a crime as far as I know. But they’re behaving wrongly and doing so essentially through bullying on a corporate scale, financed (in part) with the fortune they made off a patent that should never have been issued. They absolutely need to be placed in check, and the intangible harm they’re doing, which the average person can’t appreciate, needs to be stopped. Also, as I pointed out in part 2, WotC would be doing themselves a favor by abandoning their copyright misuse. A much larger threat looms over their work, and if they don’t get ahead of it, it could potentially “bankrupt” the marketability of 5th edition.

But they won’t, so what happens if this goes to trial and I get a judgment expressly excluding stat blocks from copyrightability. What then? Does WotC go bankrupt? Does the entire industry go bankrupt? No. What happens is this: WotC must stop misusing their copyrights, and once they stop, they get their copyrights back. Their artistic folk will never have to stop doing the creative work they do, no one will lose their job (except perhaps their lawyers and me for spending too much time on this matter; who can’t get behind that?), Adventurer’s League will keep going, and everyone will be happy.

Does anything else happen?

I’m in It for the Money and I’m Full of It

Again, let’s say this goes to trial, and I earn a 100% victory. What do I win? The judge or jury will give me the whopping award of $0.00. That’s zero dollars. For people overseas, that amounts to zero euros and zero yen. For the privilege of earning that cash reward (I won’t take a personal check), I get to invest in the equivalent of as much as $500,000 in billable legal hours (based on Gary Gygax’s atypical experience representing the upper end of costs).

If I’m not doing this for the community and the industry, I’m not sure who I’m doing it for.

Cognitive Dissonance

A recently published article had a quote in it that’s essentially what’s been bouncing around in my head as I wrote these posts. The article is about the origins of D&D, and the premise of Rob Kuntz is that a significant part of the public has mistakenly believed that Gary Gygax was the single focal point for the origins of role-playing games. In making his case, he said:

“Humans do not like to admit they’ve been hornswoggled, lied to, cheated, or fooled.”

Absent any genuine counterarguments to my piece, and in light of the genuine anger some people have expressed towards me online, I suspect this is the basis of the resistance I’ve seen over the years in my conversations of the OGL. People not only assume that no legal challenges must mean there’s nothing to challenge, but also that they couldn’t possibly have been so very wrong about the OGL for so many years. They can be, and they were.

By all means, if you think I’m wrong challenge me, but don’t assume I’m wrong just because you don’t like it. The consequences to the industry and community are too great for any of us to allow our biases or emotions to guide our approach to this topic.

Consideration in the OGL

I want to add a little more depth to my claim that the OGL lacks consideration. As you may recall, consideration is legalese for something of value that passes between the parties to a contract. If homeowner pays painter $3,000 to paint homeowner’s house, then the painter receives $3,000 as consideration, and homeowner receives a paint job as consideration. Without both parties receiving consideration, the contract isn’t legally enforceable.

The OGL lacks consideration. In a nutshell, the OGL creates two classifications of subject matter: the OGC (defined as the “game mechanic”) and the PI (defined by a list of different elements of the game). The OGL claims to license the OGC but not the PI. This is problematic because the OGC doesn’t contain anything in it that’s copyrightable. That is, it’s well-settled in American copyright law that game mechanics aren’t copyrightable, which means that the entire public already “owns” (so to speak) the game rules, so an attempt by the OGL to license OGC fails to provide the public any consideration.

The issue, however, is that the OGL never specifically mentions, “the specific way in which the game rules are expressed.” That’s something that is copyrightable. For example, on page 197 of the Player’s Handbook, WotC provides several paragraphs of text organized by several subheadings describing what happens when a player’s character drops to 0 hit points. Everyone is welcome to express the 5th edition rules for dropping to 0 hit points, but probably not in that particular way (or any way in which is substantially similar to it). So, does the OGC include “the specific expression” within the definition of “game mechanic”?

I don’t think so. First, it’s clear that the listing in PI is an attempt to grab anything that falls under the realm of either trademark or copyright. Moreover, that list contains several vague terms that clearly are meant as “catchalls” to grab anything copyrightable that isn’t expressly listed. On the other hand, the OGC goes on to define what is meant by game mechanic, and the list consists of terms (and synonyms) that are used for the subject matter of patents (methods, procedures, processes and routines), and then qualifies that to exclude any aspect of the game mechanic that falls under the category of the comprehensive list of copyrightable and trademarkable subject matter. In this case, the layman’s definition of mechanic matches the legal definition, so there’s no reason to believe that the absence of “specific expression” was unintentional. Still not convinced? Here’s an exceprt from the 2004 FAQ, which has never been retracted by WotC:

Q: Is Open Game Content limited to just the “game mechanic”?

A: No [but] Wizards, however, rarely releases Open Content that is not just mechanics.

It seems WotC’s intentions have never been to “license” more than something they have no power to license, the actual mechanic itself. They acknowledge that they could license more than the mere mechanic but state they rarely do that. At the very least, this represents an ambiguity that would be interpreted against WotC.

It’s easily possible that a court would disagree, but that would create a whole host of issues for both WotC and the industry in general (all the fault of WotC). As mentioned in Part 3.5, if the OGL were to contain consideration within it, then the OGL itself represents copyright misuse, without having to look at the SRD or WotC’s other behavior. This means that when WotC intimidated the industry to include the OGL in their products, those other game designers were placed in an impossible position: Get sued by WotC or engage in copyright misuse that prevents them from enforcing their own copyrights.

I’ll never include the OGL in any of my publications.

No More Posts

I don’t plan on a part 5, 6, or 127 for this series, but this is an ongoing conversation. Feel free to comment here or on Twitter.